Everything is an ad space

The future of advertising is indistinguishable from content

My struggle with today’s solution to Strands on The New York Times Games made me realize I was solving an ad (spoiler alert). And at CES this week, Roblox announced new ad formats. It's part of a broader trend: companies figuring out how to integrate ads into emerging forms of media without giving users the ick.

From Roblox this week:

As we kick off 2026, we’re scaling our advertising platform with new formats and tools designed to solidify Roblox as an essential channel where brands can measure results and build authentic, lasting connections with Gen Z and Gen Alpha users. At CES, we announced a brand-new homepage format, expanded our programmatic partnerships, and showcased strategic brand partnerships that provide marketers with more control, transparency, and options to drive meaningful results.

We want to transform how brands engage with audiences, moving beyond static ads to deliver truly immersive, user-first experiences. We’re focused on driving both reach and meaningful results by introducing premium formats that launch seamlessly, and are native to the platform and valued by our community.

Roblox has previously experimented with more typical mobile ad formats. In the hit game Grow A Garden, for example, users can choose to watch a 6 second video ad instead of waiting 3+ minutes for their seeds to restock at the seed shop. Roblox calls this format rewarded video ads:

Rewarded Video ads enable users to opt in and watch up to 30-second full-screen video ads within immersive Roblox games and experiences. In return, users receive in-game benefits from the creators of these games and experiences, also known as the ad publishers. Early tests show an average completion rate over 80%, with select experiences seeing completion rates over 90% as users saw the value in rewards, such as power-ups or in-game currency, and considered these ads additive to their overall experience.

The history of advertising in video games can be traced back to Tapper, an arcade game published in 1984 by Bally Midways that was sponsored by Anheuser-Busch and tasked players with slinging Budweiser to demanding customers. The game was originally intended to be distributed in bars, but was subsequently transformed into the un-branded, more teen-friendly Root Beer Tapper for arcades.

In 2000, Sega ported the racing game Crazy Taxi to the Dreamcast and expanded in-game destinations to include KFC, Pizza Hut, and a Levi’s store. In contrast with Tapper, the product placement in Crazy Taxi was subtle. Sega introduced the possibility for integrated ads. The product being advertised wasn’t the basis for the game, but was instead believably integrated into the fantasy of the game itself.

More recently, with Fortnite, Epic Games has fully embraced this integrated, native ads model. New seasons of Fortnite regularly feature branded collaborations in the form of custom skins, items, and locations. This growing list of companies is wide-ranging and includes Marvel, DC, Ralph Lauren, Nike, John Wick, Resident Evil, WWE and most recently, The Simpsons. From Fortnite’s press release in November:

Drop from the Battle Bus into... Springfield? The 80-player Springfield Island features a fast-paced, back-to-basics Battle Royale experience straight from the minds behind The Simpsons. Giant donuts will fall from the sky and angry clones will roam the streets, but don’t worry, Homer Simpson is in charge. Check out Delulu for new Simpsons weapons during the Season and prepare for a month of gags, gadgets, and Simpsons animated shorts!

Advertising in games isn’t without its critics. In 2023, Ubisoft faced backlash for placing a full-screen pop up ad in Assassin’s Creed Odyssey. As The Verge explained:

Ubisoft is blaming a “technical error” for a fullscreen pop-up ad that appeared in Assassin’s Creed Odyssey this week. Reddit users say they spotted the pop-up on Xbox and PlayStation versions of the game, with an ad appearing just when you navigate to the map screen. “This is disgusting to experience while playing,” remarked one Reddit user, summarizing the general feeling against such pop-ups in the middle of gameplay.

In the case of Assassin's Creed, the ad wasn't even for another product but for the latest game in the franchise itself. The outcry from players is understandable. Part of the appeal of a AAA game like Assassin's Creed is full immersion in its fantasy world, and a fullscreen pop-up breaks the fourth wall. Had Ubisoft natively integrated the ad into the game itself, perhaps as an NPC or location, players might not have felt swindled. Instead, Ubisoft broke a long held, unspoken agreement: buying a premium game means no ads.

This cynical view of advertising is shared by critics across other industries. According to Ethan Zuckerman, advertising is the “original sin” of the web. As Ben Thompson quotes Zuckerman, an associate professor of public policy, information, and communication at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, in his article The Agentic Web and Original Sin:

I have come to believe that advertising is the original sin of the web. The fallen state of our Internet is a direct, if unintentional, consequence of choosing advertising as the default model to support online content and services. Through successive rounds of innovation and investor storytime, we’ve trained Internet users to expect that everything they say and do online will be aggregated into profiles (which they cannot review, challenge, or change) that shape both what ads and what content they see. Outrage over experimental manipulation of these profiles by social networks and dating companies has led to heated debates amongst the technologically savvy, but hasn’t shrunk the user bases of these services, as users now accept that this sort of manipulation is an integral part of the online experience.

Thompson, by contrast, views internet advertising as a win-win-win for both users, content makers, and advertisers:

The original web was the human web, and advertising was and is one of the best possible ways to monetize the only scarce resource in digital: human attention. The incentives all align:

Users get to access a vastly larger amount of content and services because they are free.

Content makers get to reach the largest possible audience because access is free.

Advertisers have the opportunity to find customers they would have been never able to reach otherwise.

Yes, there are the downsides to advertising Zuckerman fretted about, but everything is a trade-off, and the particular set of trade-offs that led to the advertising-centric web were, on balance, a win-win-win that generated an astronomical amount of economic value.

I agree with Thompson here. Ads are not inherently bad. They enable the creation and distribution of content at a scale that simply wouldn't be possible through paid models alone.

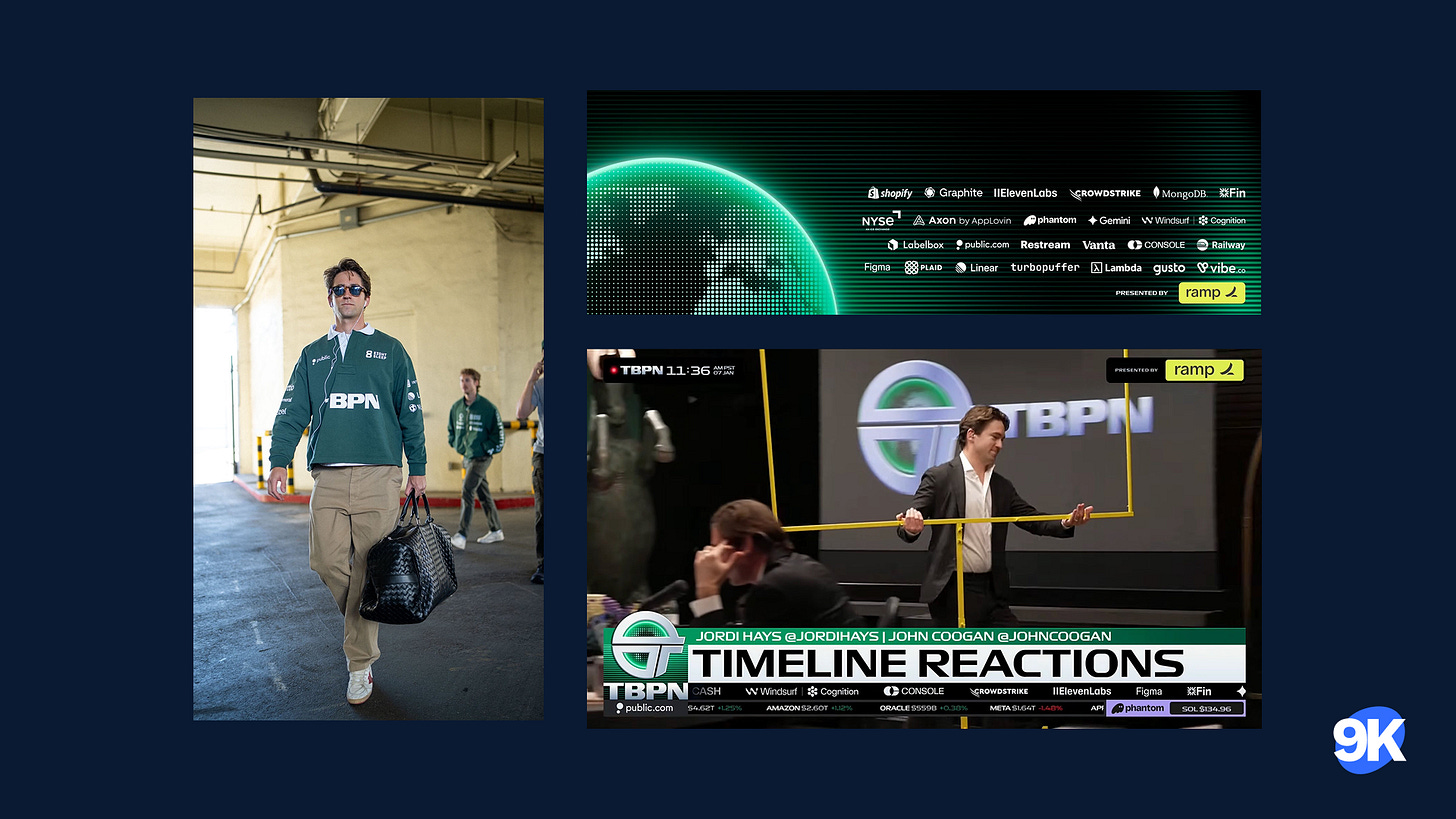

Some recent internet-native media companies have fully embraced ads in what feels like a contrarian move amidst popular culture's largely cynical view of advertising. Take the live business and tech podcast TBPN, for example, which treats its content like the surface of an F1 car. Since launching in October 2024, TBPN has inserted ads anywhere and everywhere: beneath their live news ticker, on their X banner, and even scattered across the sleeves and shoulders of their limited-release rugby shirt.

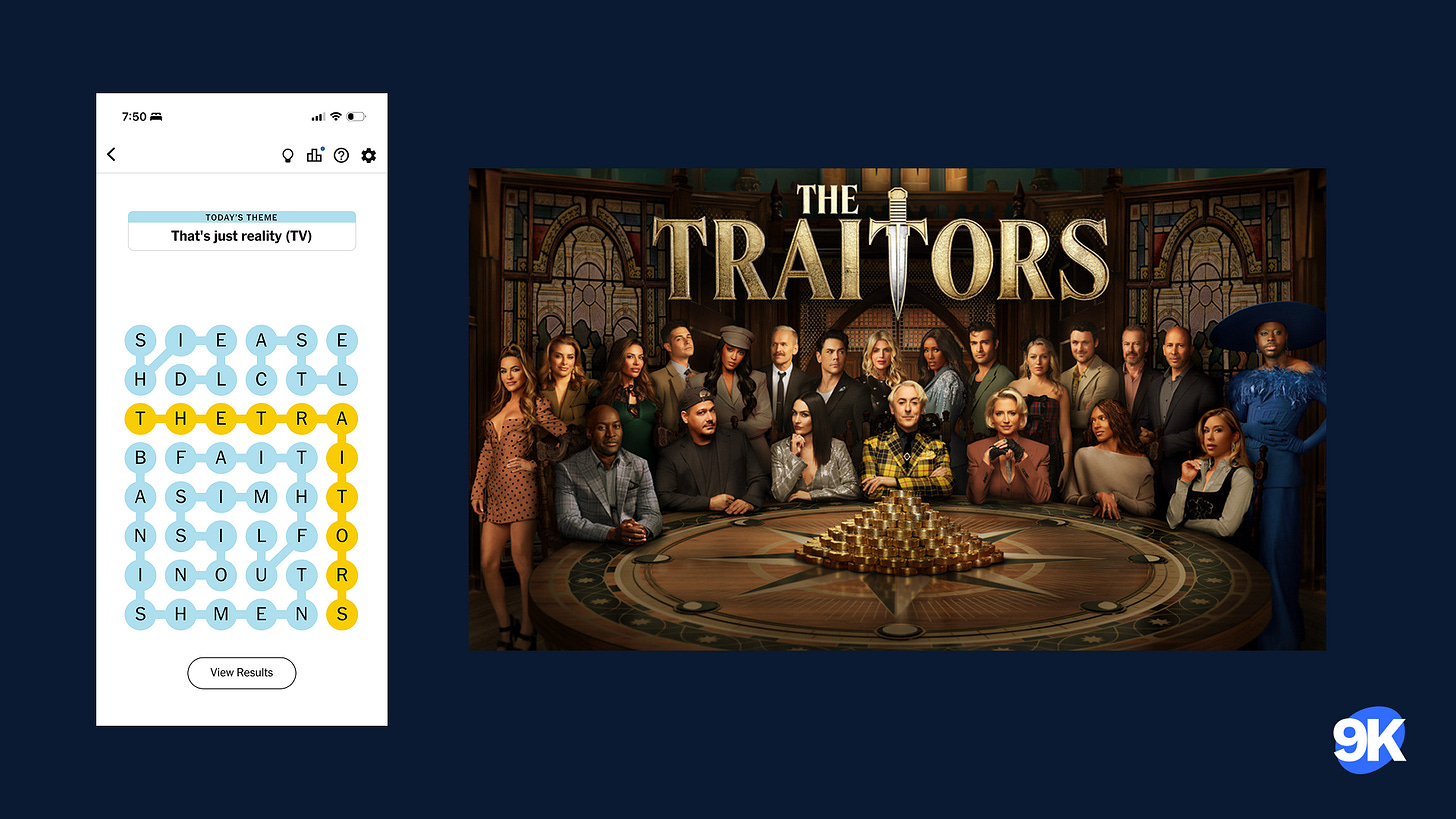

Today’s answer to The New York Time puzzle game Strands presents us with a novel integrated ad format. Well, at least I’m pretty sure it’s an ad. Solve the puzzle and you’ll find that the answer was themed around The Traitors, which turns out to be a show (I had to look it up) with a new season conveniently dropping the same day on Peacock.

In a 2023 feature for Vanity Fair, an NYT staffer said “Times is now a gaming company that also happens to offer news.” The team at NYT Games seems to have a deep understanding of their audience and format. Play the games regularly and you’ll find yourself opening up a tab to search words you’re unfamiliar with. The ad for The Traitors takes advantage of this: a significant portion of players probably haven’t heard of the show, and for those who are already fans, they get the satisfaction of solving a puzzle themed around a show they like. The success of this ad format lies in its smooth integration and novelty. If the puzzle quality drops or promotion-themed puzzles become too frequent, NYT Games could risk losing players’ trust.

Reach a certain scale and ads become inevitable. As The Information reported a couple weeks ago, even OpenAI, which has been publicly resistant to ads, is changing its tune:

Publicly at least, CEO Sam Altman has downplayed OpenAI’s desires to be an advertising powerhouse. But over the past year, OpenAI has been staffing up with digital advertising veterans and adding shopping features that could be springboards into retail-focused ads.

The company sees an opportunity to create a new type of digital ads, said another person with knowledge of the effort, rather than simply replicating existing formats like social media ads. OpenAI collects a lot of information about users’ interests from detailed chats, and has considered whether ChatGPT could show ads based on that history, The Information has previously reported. Analysts and ad industry executives say that ChatGPT conversations where users are clearly looking to buy something could be an advertising goldmine.

The surface of advertising will continue to expand and evolve. Whether users feel tricked or immersed depends entirely on the quality and integration of the ad itself.